Jungles that hide Penang’s forgotten colonial dams

The dams of Cherok To’ Kun and Bukit Seraya continue to stand amid encroaching forests in secret testimony to the dedication of their builders and operators from a bygone era.

Soon after starting a hike up Bukit To’ Kun from its base at the Bukit Mertajam recreation park, one treads through a narrow earthen path surrounded by the hill’s dense forest. Newcomers along this trail who think that they have left any remnant of civilisation behind are then in for a surprise. The woodland suddenly opens up to the sight of an enormous concrete wall of an abandoned dam.

Built by the British in 1939, the Cherok To’ Kun Dam is one of Penang’s forgotten colonial engineering legacies. Its now vacant reservoir carved out of a large hillside valley has been reclaimed by the jungle, and overgrown with grass and trees. But the giant arching wall with its high parapet railings and central observation turret looms sturdily like an edifice that refuses to allow the encircling wilderness to consume it.

Intriguingly, the structure is not the only dam in the vicinity to be neglected over time. There is an even older disused British reservoir that has remained isolated for decades, unknown to the rest of the world, in the largely inaccessible jungle of Bukit Seraya about a mile away.

What makes the dam interesting is that it was constructed, on a daunting forested slope 337 metres above sea level, to supply water for the steam rail locomotives that plied from Bukit Mertajam town.

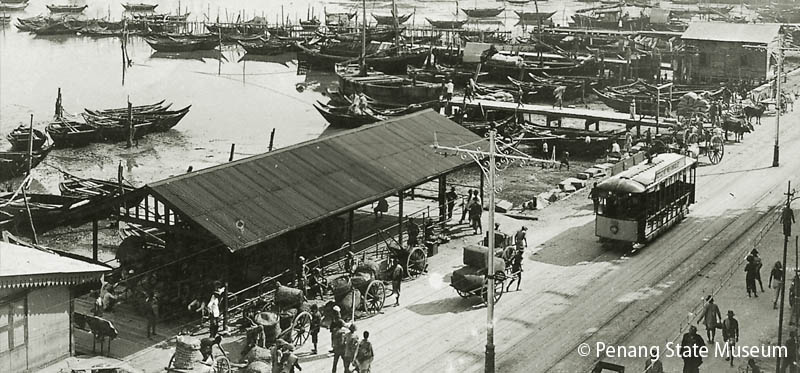

Indeed, Bukit Mertajam witnessed a population explosion after the British administration built a train station there for its rail line, installed between 1912 and 1915 to link the town to Alor Setar in Kedah. The train network, which also connected to Siam further north of Alor Setar, spurred a boom in local commerce, especially in the trade of consumer goods and minerals to and from Bukit Mertajam.

The town grew at such a rapid pace that despite there being two existing dams in Seberang Perai – the Bukit Panchor Dam meant mainly for irrigation was built in 1888 and the Berapit Dam in 1898 – residents in the area began to face water shortage. The situation became more acute due to a drought in 1926.

According to archival information provided by the Penang Water Supply Corporation (PBAPP), an investigation was carried out to determine a suitable site for a new dam. It led to Cherok To’ Kun, on the opposite side of the hill from Berapit, being identified. However, although a provision of $800,000 was made in the Colonial Estimates of 1927 for the project, for some unknown reason it did not take off until 1937.

The Cherok To’ Kun Dam with a capacity of 18 million gallons was completed in two years under the care of A.C. Wilson, the assistant engineer of Bukit Mertajam, at the cost of $813,000. It was 50 feet high and 500 feet in length and provided average flow of 500,000 gallons per day and dry weather flow of 200,000 gallons per day. At the same time, the one million gallon a day Bukit Mertajam Treatment Plant was also completed at the cost of $250,000.

The water shortage of the early 1920s must have also caused problems to the rail service which used steam locomotives. The Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR) therefore decided to construct its own dam to supply sufficient water to its trains in 1926. When completed, the Bukit Seraya Dam provided water for locomotives in Seberang Perai via a 10-inch wide pipeline and also a rail line of its own that traversed along the hill’s slope to its base.

In 1962, five years after independence from the British, the FMSR was renamed Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM). Following this, the dam and its surrounding hill were placed under the Malaysian government’s Railway Assets Corporation. There are signboards today at the base of Bukit Seraya informing that the area is a property of the corporation under the Ministry of Transport.

The dam itself is not easy to reach because it is surrounded by immense jungle vegetation without any clear paths. A team of trekkers that managed to access it in January 2018 took seven hours to find it. In December 2018, the photographer Adrian Cheah followed Penang Hikers on a 4-hour hike from Bukit To' Kun to Bukit Seraya.

Photo above, middle from left: Mr Sim, Mr Ang and Mr Luah from Penang Hikers.

The Seberang Perai Municipal Council’s (MPSP) heritage unit chief Ahmad Nasyaruddin Ismail was reported by Bernama in 2016 as saying that several artefacts like old screws, rail fragments and components from locomotives have been found on Bukit Seraya. Villagers around the hill recounted that many of these metallic remnants on the floor of the forest were pilfered by foragers in the 1980s.

Interestingly, Ahmad Nasyaruddin also said pieces of raw iron have also been found, igniting speculations that there could have been mining activities taking place on the hill in the past.

The mystery behind the place does not end there. Villagers also claim that unexplained supernatural incidents have taken place in Bukit Seraya. In 2008, a TV3 crew accompanied by some villagers venturing into the forest in search of the dam and the rail line lost their trail and spent some time nervously trying to find their way out.

Trekkers have also reported encountering a strange waterfall that looks like an old man as it has thick roots of trees growing down along its cascade. The fall has been named Tok Janggut, which in Malay means “bearded old man”.

The dams of Cherok To’ Kun and Bukit Seraya were completed just before the outbreak of the Second World War and the violent Japanese conquest of Malaya in 1941. Just as the dams are now forgotten, the efforts of a number of local individuals who worked hard to maintain water supply to the people during this trying period have also been neglected over time.

According to PBAPP’s archives, Penang’s water supply system suffered substantial damage during the early part of the war as a result of bombings. Although essential repairs were done and supplies restored, the lack of materials hampered efforts to maintain the system in proper condition.

As control by the Japanese was nominal, it was up to a few local workers to try to keep the system in order on a daily basis. These forgotten heroes included Goh Heng Chong who managed the water supply system in George Town during the troubled times, and filter plant superintendents Kanagasabai and Mr K.T. Arasu who handled the system in Seberang Perai.

-------------------------------------------

With appreciation to Dato’ Jaseni Maidinsa, chief executive officer of Penang Water Supply Corporation, for assistance in the research for this article.

-------------------------------------------

Written by Himanshu Bhatt

Photographs © Adrian Cheah

© All rights reserved.