Cherok To’ Kun’s healing village air

The ancient village with forgotten intrigues of the past today embodies the rural and natural charm of Bukit Mertajam.

More than a century ago, there lived at the end of a rural path south of Bukit Mertajam town a highly respected elderly Siamese healer named Kun. Known for his medicinal and shamanistic abilities, Dato’ Kun or To’ Kun as he was called, was sought by many who made their way to his quiet alcove near a foothill for treatment of various ailments.

In Malay, such a cul-de-sac at the end of a thoroughfare is called “cherok”. In modern times it is spelt “ceruk”, just as “dato’” which means grandfather is now commonly spelt “datuk”.

While the legendary soothsayer is largely forgotten today, the name of the area around which he lived has remained in his honour as Cherok To’ Kun. The spelling has been varied over the last few decades, with some signboards and other references putting it as Ceruk Tok Kun or Cherok Tokun.

The settlement is said to have begun in the 1880s when the early inhabitants tilled the land for agriculture and reared buffalos, cows and fowls. Herds of buffalos, a rare sight anywhere in Penang today, can still be seen grazing on the lush grasslands around this area.

Osman Ibrahim, who chairs the Cherok To’ Kun village development and security committee, remembers hearing about Kun from old people in the neighbourhood after his family settled there seventy years ago.

Fondly known to locals as Pak Teh Man, Osman lives in Cherok To’ Kun Bawah, or “lower Cherok To’ Kun”, west of the verdant Bukit Seraya hill that looms near his house. The other villages in the vicinity include Cherok To’ Kun Atas (upper Cherok To’ Kun) closer to the hill, and Kampung Teluk Bukit (literally meaning “village at the bay of a hill”).

Besides Bukit Seraya there is the much larger Bukit To’ Kun, also known as Bukit Mertajam hill, which is today a protected forest reserve and popular recreational site, especially among hikers.

Both hills have dense tropical rainforests that are great natural water catchments. It is no wonder that the former British colonialists chose to build not just one but two reservoirs around the hills. Both have been decommissioned. The Bukit To’ Kun dam is easily accessed from the entrance of the Bukit Mertajam recreation park while the one on Bukit Seraya can only be reached through a difficult jungle trek that takes some hours.

Each reservoir was called “kolam” in Malay. Hence the name of the artery that leads towards the recreation park from the busy trunk road of Jalan Kulim is till today named Jalan Kolam.

The entire area is characterised by its immense greenery. It has a refreshing humid atmosphere sustained by cool winds that pass down the hills and through the lowland villages. It is also full of orchards and gardens, with people commonly planting fruit trees such as the durian, rambutan, nangka and cempedak. Che Mat remembers that when the reservoirs were still in use in the 50s there were many paddy fields along the valleys due to the copious water supply that they enjoyed.

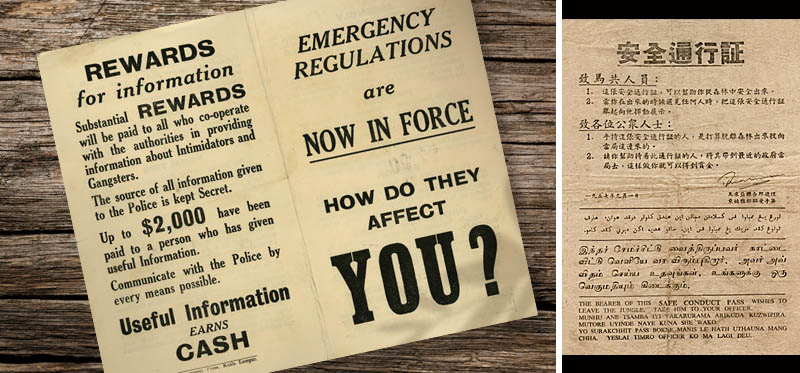

The existence of the dams was also a factor that contributed to heightened British security presence here during the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960, a period which saw a protracted violent conflict between communist guerrillas and the colonial government across Malaya.

The forest in the area was then connected to wooded terrains in northern Perak, stretching all the way until Sungai Siput, where the communists operated in clandestine and planned their attacks. There was deep anxiety among the colonial regime that attacks would also be made on the two reservoirs to cripple the sensitive public infrastructure in a bid to launch an assault on Bukit Mertajam.

This led to the British establishing military barracks in Cherok To’ Kun and stationing a large number of armed personnel to guard the dams and monitor the jungles.

The Emergency was a dreadful period for the residents as they lived in fear of being shot at by the insurgents. It was suspected that the communists were being provided with essential supplies from sympathisers around Bukit Mertajam who rendezvoused with them at these forests. The rebels themselves were wary of anyone detecting them and informing the authorities.

Osman remembers that the local police lockups were brimming with suspected communist activists during this time. He had been to the Bukit Mertajam police station as his father was a sub-inspector with the force who had moved here from Balik Pulau in 1952, serving under a British officer in charge of police district (OCPD).

Development later took place at a rapid pace after peace was restored following Malaysia’s independence. Among these, the landmark Cherok To’ Kun mosque, which was opened in 1966 by the then deputy prime minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein, still stands on the other side of Jalan Kulim, across from the Bukit Mertajam recreation park.

The other famous religious site in the area is the 170-year-old Church of St Anne further west and nearer to town, whose annual novena in July attracts thousands of pilgrims from around the region.

Behind the mosque is a lengthy village road quaintly named Jalan Kilang Ubi (“potato factory road”) after an old Malay factory there that produced fried potato and tapioca chips. The neighbourhood here has numerous traditional Malay village houses sheltered under tall coconut trees and surrounded by groves of rambutan, papaya and ciku fruit trees.

Indeed, the entire area radiates with an idyllic natural ambience so rejuvenating to the senses that one cannot help but wonder if the spirit of the once renowned healer Kun is still alive and well amid the air here today.

-------------------------------------------

Written by Himanshu Bhatt

Photographs © Adrian Cheah

© All rights reserved.